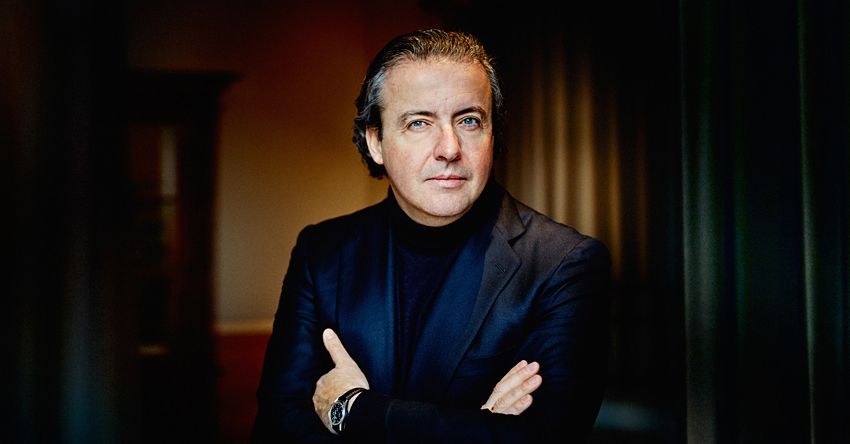

Juanjo Mena: “Seeking the truth in music requires real dedication”

* Click aquí para la versión en español

Having recently reached the age of fifty, Spanish conductor Juanjo Mena (Vitoria, Basque Country, 1965) faces the maturity of his career, with such important engagements as his Berlin Philharmonic debut, in which he’ll conduct works by Debussy, Ginastera and Falla. The BBC Philharmonic’s Chief Conductor since the 2011-2012 season, he regularly collaborates with some of the most prestigious European and American orchestras, and of course the orchestras from his home country, including the Spanish National Orchestra, with whom he has a close link.

First of all… How are you getting on? I guess you’re excited and eager to face your busy forthcoming schedule?

I feel fine. My recent years of work have helped to provide me with the self-confidence to look ahead and feel that the best is yet to come. The highlights always stand out, such as conducting in New York a month ago, and looking forward to Berlin and Rotterdam. But my work at the BBC is always waiting for me every week; we finished a run of three concerts yesterday, and today I’m studying for the next two separate programmes that we’re performing this week.

Let’s talk about conducting BBC Philharmonic… I remember you talking about the high-level performance control of the orchestra, as well as the need of a boost to explore boundaries.

I’m aware that my comments about the BBC may have been misunderstood; I guess I didn’t explain it properly. I’m talking about an orchestra whose sight-reading is top-notch; they can play anything you put in front of them to a very high level, hence the need of a boost to explore boundaries. The musicians work very accurately on the score and they relish being challenged. It’s a Radio Orchestra so each and every thing is written down and marked in the score; I’m used to working under pressure, the pressure of the radio the recording sessions. We have just performed three dates, with the same programme, and last Friday the BBC broadcast the concert in Nottingham live on air, and yesterday’s concert in Manchester was recorded for later broadcast. The microphones are always there, and the orchestra knows that this experience won’t just be lived by the people who are attending the concert. It’s very hard work, and within this context, what I wanted to say is that they are therefore technically very secure - they have to be. For you to have an idea of how we work, we go into the rehearsal room on Monday, we have two rehearsals, each of two hours, and a general rehearsal on Tuesday at eleven o’clock in the morning, then we play live on air in the studio at two o’clock in the afternoon; this is a full programme, for instance, an overture and then a concerto, it may be a Saint-Saëns concerto for example, and finally something like Bartók’s ‘The Wooden Prince’ in its entirety. And we’ve got one and a half days to get it ready for radio. Next, on Wednesday, we are back in the studio, possibly recording something that we performed the day before, this time for the Chandos record label. And then on Thursday we start working on Saturday’s programme when we play at Bridgewater Hall in Manchester, our own Hall, and the best in England. But we’ve also been contracted to perform in another city in the north of England; we may be regarded as “BBC North” – we don’t go up to Scotland but we serve the whole of the North of England. We’ve been in Nottingham, Huddersfield and Hanley this week… and the programme must be different each time, as people may decide to travel from one city to another to attend the different venues. So on the Thursday we start rehearsals for both programmes and the next day we perform live in Hanley, rehearsing at three o’clock in the afternoon and performing again in the evening that day. We may easily perform three programmes a week, so the preparation, rigour and reliability that are expected of the musicians is extremely high.

I expect the audience’s expectation is very high…

The audience also wants some interesting programmes. I once asked for some Tchaikovsky to be programmed and I was told Tchaikovsky isn’t an audience favourite here. What we really need is assortment somehow… maybe Bartók, maybe a not so well-known composer… in order to entice the public by performing something new. Next Saturday we’re going to perform a very assorted programme such as William Schuman’s American Overture, Barber’s Piano Concerto, Copland’s Quiet City and Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition. That kind of programme works here!

So you could say that these last five seasons at BBC have given you the ability to become more objective, critical and analytical?

Yes – that and working under enormous pressure. I guess I’ve doubled up my repertoire over the last five years and I’ve also performed a lot of premières, as I have done here in Spain. As my first year at BBC ended I received offers from world-renowned orchestras, even earning five times what I currently earn but turned them down because this is where I have the pressure, the microphone is always listening to me and I’m ready to record nearly at first reading, and this is where I can grow and continue my quest to discover something new. Of course I’m tired because the pressure is so great, but it’s given me more confidence in my work.

And this objectivity is how the door has been opened up for me to some of the great orchestras. My first programme conducting the Chicago Symphony Orchestra was a Nézet-Séguin last-minute cancellation. I had to conduct Tchaikovsky’s Pathétique Symphony, and I said to myself ‘Oh my God!’ as soon as I realized the orchestra had recorded the work with Reiner, Solti, Barenboim, Abbado… with everyone! And now it’s my turn. I had taken a break from the score for many years after performing it in Bilbao some years before, because I also realized I needed some more time to understand it. However, I approached it again from a fresh perspective, and was able to meet the challenge; the Pathétique became one of the successes with of my relationship with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. I just did what was written in the score, no more, no less. They were grateful to me for my efforts, as they were tired of some of the embellishments that some conductors add to the score. You know, the Pathétique can sometimes be treated like an accordion, played full of embellishments, and the more ornaments can lead to the worst listening experience. If you do what’s written in the score, it’s beautiful.

And talking about your goals and targets since you took over the BBC Philharmonic… How many of your career goals have you achieved? Is there something left to do?

I’ve managed to work at the highest possible level, I’ve gone further and I’ve understood my job in depth, I’ve realized what a radio orchestra really is, and I’ve experienced everything from a live concert to the studio, the BBC Proms and touring, I’ve travelled around Europe, Spain and most recently China and Korea with them… I mean, these are musical experiences of a high level. We’ve just performed the Leningrad Symphony, and the most wonderful thing is when the musicians look at you on stage as if to say “what just happened then?” What happened was something beautiful that can’t be explained, and then you see the audience’s reaction too… Our path is an endless quest, and the very few times you feel you reach your target, it’s such an amazing moment and suddenly you feel just like starting over that quest again and again. I was taught by three great Maestros, who still follow me now. Maestro García Asensio, who taught me such an incredible technique, all that I needed to accurately transmit the way I feel to the orchestras I work with; in return, those orchestras feel grateful to me. Following García Asensio, came Maestro Bernaola. We used to talk about orchestration and harmony. He gathered all of us together, on Saturday mornings or Sunday evenings… he didn’t care what time it was. He’d say “Which instrument is going to play this chord? What register is it going to be? How are the members of an orchestra organized on stage?”… Little by little and step by step I managed to know an orchestra in depth while being unaware of each and every thing I was learning. Finally, Maestro Celibidache, who was my greatest influence so I’m undoubtedly biased. With him I found out what creativeness meant in conducting, on a completely different level.

And now I find myself in a good place. I’m still a young conductor; I look at myself and I see myself as a young conductor even when I’m fifty years old. I feel younger than I am. I guess I’m starting to comprehend what it’s all about, and I see that I have the most beautiful twenty five years ahead of me to discover what music really is.

Let’s talk about now and then… You used to conduct and record with the Bilbao Symphony Orchestra some years ago, and right now the BBC Philharmonic is under your baton… What are the main differences?

Well, we are talking about two different worlds and two different starting points. When I started conducting the Bilbao Symphony Orchestra I tried to change discipline, rigour and took absolute control of the orchestra. I remember in one of my first seasons with them, I spent twenty five weeks with them, maybe more, with the musicians, section by section and desk by desk… as I had enough time to do it. I learnt a lot back then. And we decided to get into the recording studio as recording meant a requisite level of the orchestra regardless whether they were ready to record or not. And we did our best. I must confess that we all learn a lot as well as we improved ourselves: we had to listen to ourselves finding out we weren’t in tune, or weren’t together, and had to repeat passages; and finally we all know how to get everything right.

I also record in the studio with the Spanish National Orchestra, with whom I’ve recorded some of Joaquín Rodrigo’s pieces in the past. I was once told that we had two weeks to record the disc, and I replied that we could fit it into five days. We are all professional musicians, aren’t we? So let’s get ready. And the same story again, recording with the Spanish National Orchestra, we have recorded in very short periods of time which requires a great deal of concentration in order to maintain the focus, and sustaining that concentration over a longer period of time is not that easy. We all have learnt to get into the studio and record fast-paced and it helps our regular working week.

Regarding your own professional career… Is 2016 the crucial year for you?

To a certain extent, yes, it is. I must also recognize the significance of 2008 and 2009 when I decided to leave Bilbao behind, a bold and risky decision as I didn’t gain a Chief Conductor position for two years. But everything picked up in America around 2009 as I started conducting some of the best orchestras and right now I must admit I’m happy, because those orchestras who called me for my debuts have re-invited me. I’ve had an ongoing relationship with Boston for eight years, including concerts at Tanglewood, and with New York, where I was immediately invited for the next season after my debut; Chicago, Cincinnati, Houston… places that made me feel comfortable.

This is the year when some of my hard work will pay off alongside positive reviews and rewarding results with the BBC Philharmonic. And the Berlin Philharmonic arrives perhaps as a wonderful birthday gift. Now I’m fifty years old and feel I have enough of a career behind me to face the Berlin Philharmonic and to have something interesting to say to them. I remember when I first worked with the Bergen Philharmonic Orchestra; it was the first time I’d heard an orchestra playing together, in tune, sounding wonderful at ten o’clock on Day 1, with four days remaining to rehearse… What else could I say? What else could I suggest? Suddenly I remembered Celibidache’s rehearsals and I found out the right way: at that moment in time I discovered a new way of creating, discovering limits, searching for colours and balance - a whole new approach.

I think now is the right time to go to Berlin; it has come naturally, through a direct invitation from them. Going too soon to these top orchestras can be a mistake. I still feel like a young conductor, and probably will do in ten or twenty years time.

Regarding the current situation of conductors’ schedules, it’s been said that their schedules are so busy that they can’t work so closely with the orchestras of which they are Chief Conductor, and that very few programmes are actually conducted by them. Do you think this is an ongoing issue? How does this affect the performance of an orchestra?

Globalization tends to homogenize structures and we are not free from it. I could be working every week of the year, both with my orchestra and as a guest conductor of other orchestras. But that would be crazy, it makes no sense. I need time to study, to take a break, to share time with with my family, to cry with my children, to go for a walk, to go on holiday… but I’m aware I need conducting in my life, and occasional excessive workload may happen.

When I left Bilbao I remember I received offers to be principal guest conductor for some orchestras, being with them for a few weeks. And suddenly “with a couple more weeks each year, you could be considered for Chief Conductor”. No – I couldn’t consider being Chief Conductor working just six weeks a year. The commitment needs to be greater. Now I’m contracted to around 12 weeks per year at the BBC, but it can go up to 15 or 16 weeks with touring, and I think it’s the minimum commitment that a Chief Conductor should have.

Leaving your own stamp on an orchestra is quite a difficult job; face-to-face contact and being involved in day-to-day issues is the key, knowing people and their problems, to get and achieve the best of them… it’s such a wonderful experience; to experience the life-sharing, making mistakes and enjoying the greatest moments is also the key. I’m aware that when considering Chief Conductors the business aspects are quite important, but there are many people who set their sights very high very soon in their careers, and but I feel that in this profession, and in order to respect the music that we’re performing, a calmer, more gradual approach is required.

A new Spanish law known as LOMCE would revoke music as a compulsory subject, and many hours of tuition would be lost in both primary and secondary education. As a Spanish musician working abroad, what’s your opinion about it? What are the main differences between Great Britain and Spain?

I think there’s a huge difference. Here in Great Britain we may discuss the issue about whether music is taught in school or not, or why music isn’t taught in schools in some areas. But there are other possibilities, and so many ways to teach music, with Saturday Music School being one of them if music isn’t taught in class time, with a wide range of activities and classes being offered at weekends. In Germany music is regarded as being part of family activities.

Spain is such an amazing country. I could tell you about my professional career, or that of many other artists’ professional careers too. I was seven years old when the choir conductor, Antxón Lete, came into our classroom playing a flute to test pupils’ musical ear and voice… and everything he did, he did it for free. He took me out of classroom and asked me whether I was willing to join the choir or not. I had to ask my parents if I could as there was no musical tradition in my family, no relationship with music at all… and now you can see, my brother is a countertenor, my sister studied piano, bassoon, she conducted some choirs and she used to sing… (now she’s a chemical physicist).

And it’s such an unbelievable thing… Spain is very proud of its musicians, and a musician like me got into music thanks to a choir director who worked for free and ran a choir at Samaniego School in Vitoria (Basque Country)… and it’s the same old story, a lot of us came into music thanks to these unknown musicians who loved music. Antxón Lete made me love music, I became part of the choir and finally I applied and ended up as a student at the music conservatoire. I used to play the ‘txistu’, a traditional Basque instrument, and also I used to perform on stage as a soloist. When I was sixteen years old he asked me to attend some choirmaster classes and then I got my own choir, a female choir consisting of a hundred voices. Back then I started to realize what an ‘interchange of energy’ meant.

And as I talk about my own life you may ask yourself… Where else may you find a school choir conductor for free? I remember I used to play in orchestras as an extra musician for free, and it seems that those times are over. Now young musicians ask what the fee will be to play in a youth orchestra. In Great Britain, it’s not like that at all - young people pay to play in good youth orchestras and amateur orchestras, and only when they are considered good enough to play in a professional orchestra will they earn money.

There’s a lot to change in Spain; increasing the music provision within school hours would be the best of it all, without a doubt. But it’s not just a problem with our country, but with how society in general is changing. Subjects such as languages, history and music are left behind in order to focus on what’s ‘important’ – the measure of ‘quality’ is having computers with big screens, more IT and maths classes. My children attend a Waldorf school, they promote artistic skills and let children be children until they are ready to take the next step in their lives, not like in most of society where when you’re eight, you have a mobile phone. I ask myself… where are we going next? You go into a restaurant and everybody is talking into their mobile phones rather than speaking to each other… but I guess it’s progress! A sad progress, I think.